The Ministry of Qes Gudina Tumsa in the Kambata/Hadiya Region

Staffan Grenstedt

(Uppsala University)

Abstract: This paper highlights Qes Gudina Tumsa s efforts in the Kambata/Hadiya

region with special bearing at integrating the Kambata

Evangelical Church 2 (KEC-2), which had broken away from the Kambata Evangelical Church (KEC) in 1954, into the

Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus (EECMY). The

KEC-2 attended the annual Conference of Ethiopian Evangelical Churches (CEEC)

from 1955 to 1961, when the EECMY Home Mission with the Kambata

Home Mission Program (KHMP) was launched. Qes

Gudina s efforts in the region can be divided into two periods. The first was

in 1963 when he tried to integrate the KEC-2 into a synod of the EECMY. As we

will see, this approach generated some problems. His second attempt, together

with the Finnish Missionary Society (FMS) in 1967-69, was more successful.

Notation and Theological

Method

The footnotes at the bottom of the pages refer mainly to my Doctoral

Dissertation (Grenstedt 2000), on which I ground my

paper.[1] The title is: Ambaricho and Shonkolla From Local Independent

Church to the Evangelical Mainstream in Ethiopia. The Origins of the Mekane Yesus Church in Kambata Hadiya, published by Uppsala: Uppsala

University in 2000. For convenience s sake, I let the Ambaricho

Mountain symbolize the Kambata ethnic group and the Shonkolla Mountain, the Hadiya.

I will make use of the Theo logical Typology of the Norwegian scholar

Einar Molland and

elaborate on it for my own purpose. Turner and

Daneel have

employed Molland s typology for independent churches in a similar way.[2]

In order to characterize a Christian community, Molland identifies four basic aspects in his

structural, theological analysis: doctrine, polity, worship, and ethos.[3] There is

an organic correlation between these aspects but different communities display

a characteristic emphasis on one of them. For example, doctrine is the dominating (and unifying)

characteristic of Lutheran churches. Molland furthermore defines ethos as

a characteristic lifestyle linked to a confession. It is thus wider than

ethics. I elaborate on Molland s scheme and add relation to EECMY, ecumenism

and size as further aspects for comparison.

Historical and Ethnical Perspectives

in the Kambata/Hadiya Region

The Kambata/Hadiya

Region

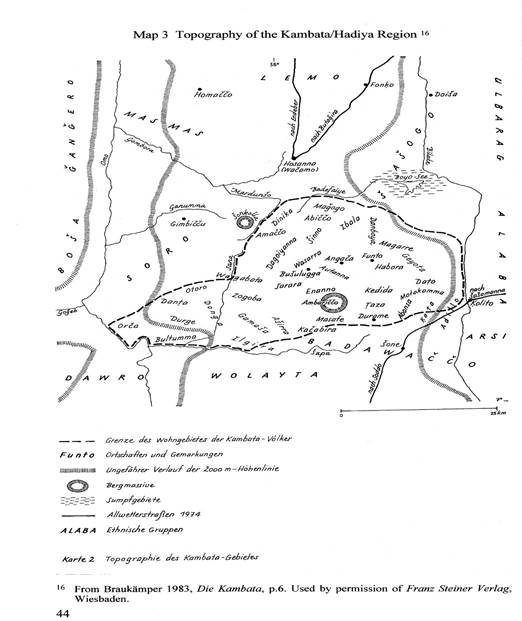

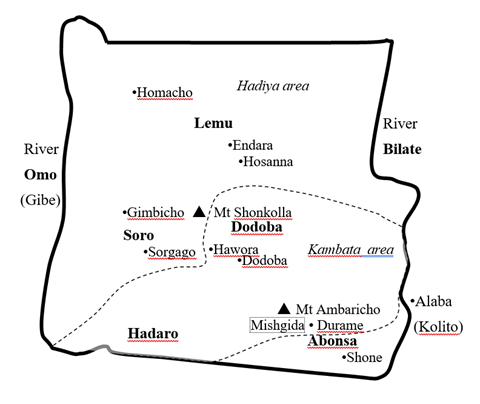

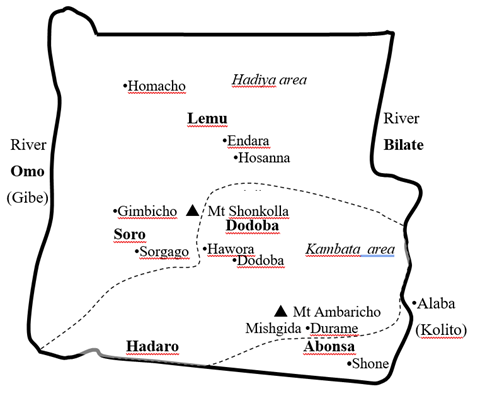

The area between the River Omo in the

west and the River Bilate in the

east, which I call the Kambata/Hadiya region, has its

own complicated history.[4] Originally

the Kambata peoples, in a general sense , were

peasants and the Hadiya were semi-nomads. Their

internal history has to be differentiated into the

history of their sub-groups. The relations between Kambata in a narrow sense and the Hadiya sub-groups Shashogo and Badowacho, for instance, were quite friendly.[5] By the end of the 16th

century one can use Kambata not only as a political

term for a people, drawn together from heterogenous groups, symbolised by the

number seven (sebat

in Amharic; lamala

in Kambatissa)

and with a king at its head.[6]

Relations between the two strongest Hadiya sub-groups, Lemu and Soro, however, have been strained from time to time, the main reason

being their need of grazing land for their herds. Soro and Wollamo became

enemies of the Kambata proper , whose kingdom started to expand c.1810. It is thus too simplistic to

talk about tensions between the Kambata and the

Hadiya just in a general sense. The situation has been more complex than that.

In fact, the Kambata peoples in many cases

complemented the products of the semi-nomadic Hadiya through their skilled

farming techniques.[7]

The good agricultural conditions in the Kambata/Hadiya

region led to a population density up to more than 300 per square km. Many

conflicts in the region were due to scarcity of land. This was also the case in

the conflicts along the southern borderland to Wollamo.[8]

Early Missionary Ventures,

Revivals and Schisms

The Sudan Interior Mission (SIM)

started its work in the Wollamo (Wolayta) region in 1928 and among the Hadiya around

Hosanna in the Kambata/Hadiya region in 1929.[9] In 1933 a station was built in Durame among

the Kambata. The missionaries were forced to leave

the two regions due to the Italian occupation in 1936 (Kambata/Hadiya

region) and in 1937 (Wollamo region). When they left

Ethiopia in 1937-38 just ten converts from the Kambata/Hadiya

region had been baptized by the SIM missionaries. Another twenty had been baptized by

Ethiopians.[10]

When the SIM missionaries resettled in Wollamo (1945)

and in Kambata/Hadiya (1946), they recognized that in

the meantime there had been a remarkable church growth of approximately 15,000

baptized members (adults), in what I hereafter call the Wollamo

Church , and approximately 10,000 in the Kambata Evangelical Church.[11] These remarkable revivals were led

by indigenous Ethiopian Christians in the densely

populated regions in southern Ethiopia.[12]

After the return of the SIM missionaries in 1946, however, there

occurred schisms within the KEC. In 1951 a group of seventeen churches broke

away from the KEC. In 1952 the two dissenting groups were reconciled. Again, in

1954 another group broke away. It is this latter group I identify as the independent KEC-2.

Evangelical Church Formation

As hinted above, annual conferences called the Conferences of Ethiopian

Evangelical Churches (CEEC) were arranged by Ethiopian

Evangelicals from various parts of Ethiopia in 1944-63.[13] They were signs of the ecumenical climate, which prevailed among Ethiopian

Evangelicals after the Italian occupation. Owing main ly to later missionary

influences, causing a growing denominationalism, the importance of the CEEC

decreased. In 1957 the SIM-affiliated groups stopped attending the CEEC

meetings in Addis Abeba. This is a clear indication that the Ethiopian

Evangelical movements went in different directions.[14]

Instead of

firmly establishing one united Ethiopian Evangelical church ( EEC ) or a

federation of Ethiopian Evangelical churches, the road to establish

confessional churches was set. The evolving Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus, which traces its roots via the

CEEC to the Evangelical Pioneers from the 19th century

and to even earlier influences, established itself in 1959.[15]

SIM

missionaries and SIM-related churches, like the KEC and the Wollamo

Church, met in May 1956 and founded the

Fellowship of Evangelical Believers (FEB). The FEB, which from its

inception had a doctrinal statement, started to meet annually and was later

joined by churches connected to the Baptist General Conference Mission.[16] The Fellowship of Evangelical

Believers was registered with the Ethiopian Government in 1964.[17] From 1969 the name the Kale Hiywot Churches (KHC) began to be used by members of

SIM-related churches.[18]

The

Presbyterian Bethel Church, which was initiated by the

American United Presbyterian Mission (AUPM), preserved its Ethiopian

Evangelical legacy and attended the CEEC until 1963. In 1974 it became a part of the

EECMY.[19] A common experience, which both the

EECMY and the KHC share as the two dominant Evangelical churches

in Ethiopia, is a long-felt critique from the venerable EOC.[20]

The KEC-2

Evolves as a New Local Independent Church

As will be recalled, Ato Biru Dubale was the

strong leader in the early Wollamo Church. His new indigenous church in Wollamo started to grow when it received financial support

from the Swedish Mission Bible-True Friends (SMBV) in 1951. In 1954-55 it comprised approximately

thirty to forty congregations.[21] The Norwegian Lutheran Mission

(NLM) policy of paying salaries attracted KEC

members and generated discussions between the KEC and the SIM. Even if an

agreement was reached between the NLM and the SIM in 1953, the situation was

still tense. The presence of the Seventh Day Adventists (SDA) in nearby Shashamene, and its intensified contacts in the region,

and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church s (EOC) attitude towards Evangelicals, did not

improve ecclesiastical relations. To use an understatement: religious dynamics

inside the region were complex in 1953.[22]

A

discontented group in the KEC reacted against the KEC s sharpened discipline on

drinking since 1953. It looked at the church of Ato Biru Dubale, and in 1953

several deputations from Kambata visited the NLM center in Sidamo and

asked for an alliance. They were, however, let down by the Norwegians, who were

more concerned about comity principles than the SMBV.[23]

It seemed

as if the new dissenting group in the KEC was very concerned with gaining an

outside supporter. It was pressed from two sides: the KEC (SIM) and the EOC. It understood that it could hardly

survive on its own and was discussing . . . how to obtain the missionaries who

could support their work .[24]

It was this

discontented groupthat I identify as the evolving Kambata Evangelical Church 2. It had its strongholds around

Dodoba, close to Mt. Shonkolla, and in Mishgida

(Durame), close to Mt. Ambaricho. Two of its early leaders were men

of some wealth: Ato Mersha Tesema from the Dodoba

area and Ato Ashebo Wolecho, a coffee trader from Mishgida

. Ato

Mersha was active in connection with the Addis Ababa Mekane

Yesus (AAMY) reconciliation attempt of the KEC in 1952.

Furthermore, he presented a letter to the Emperor on

religious freedom. He obviously mastered Amharic

and became the new spokesman of the KEC-2.[25]

The

SIM-related churches had probably received special invitations to the 1955 CEEC to discuss and decide on a federation among

Evangelicals in Ethiopia. This was also in the interest of the evolving KEC-2.

The determined preparations of this dissenting group in 1954 to attend the 1955

CEEC in Addis Abeba under the leadership of Ato

Mersha, as a church in

its own right separated from the KEC, marks the final split within the

KEC and the birth of the KEC-2.

The KEC-2

primarily reacted against the KEC (SIM) foreign cultural pressure on drinking, that is on ethos, otherwise it was very similar to

the KEC. Moreover, it was founded in Africa, by Africans,and primarily for Africans. The KEC-2 had

the characteristics of a local African Independent Church fighting for its cultural freedom.[26]

After

breaking away from the SIM-related KEC, the KEC-2 found a platform in the CEEC from 1955 onwards. When the EECMY was founded

in 1959, one of the big challenges of this church was how to relate to the

KEC-2. Describing its engagement in the KEC-2 as a Home Mission , the EECMY deliberately bypassed

missionary comity principles and involved itself in the Kambata/Hadiya region.[27] In 1962 the Kambata

Home Mission Program (KHMP) was launched. It was mainly

financed by the Lutheran World Federation (LWF). The KEC-2 gained a new status as

the Kambata Synod in the EECMY in 1969 and the Finnish

Missionary Society (FMS) became its supporting mission. The

Kambata Synod changed its name to the South Central Ethiopia Synod (SCES) in 1977. It was later amended to the South Central Synod (SCS) in c.1983.[28]

The EECMY s

Home Mission in the Kambata/Hadiya Region

Ethiopian Evangelical Solidarity in Practice

The EECMY Executive Committee was called at short notice for its second

meeting on June 12, 1961. The main issue was to discuss and come to a final

decision on questions relating to the KEC-2. The four founding synods of the

EECMY were represented by eight men. In addition to the five EECMY Church

officers, Qes Badima Yalew had been

invited as a guest.[29]

The history

of the Kambata churches was presented to the EECMY

Executive Committee in four ways:

1.

The EECMY President, Ato

Emmanuel Gebre Selassie, gave a short introduction on

developments from 1947 to 1961. These concerned the conflicts in the KEC and

the Kambata churches petitions to the CEEC and to the EECMY. The final decision on how to

relate to the KEC-2 was now going to be made, he declared.

2.

The report of the Special Commission to Kambata was

handed out to the Executive Committee s delegates and read, probably by Ato Amare Mamo. He was the only one of the Special

Commission attending the meeting.[30]

3.

The CEEC minutes from 1947 to 1961 were read in short.

4.

Qes Badima Yalew was asked to

speak on what he knew of the matter.

This was the background given to the Executive Committee to act upon.

Qes Badima and Ato Emmanuel

were indeed the right men to relate the history of the CEEC contacts with the Kambata

churches. The written report of the Special

Commission to Kambata provided a fresh illustration

of the situation.

The EECMY

presentation provided an elaborate basis for decision-making. The importance of

the CEEC legacy to the EECMY was highlighted by the

reading of the CEEC minutes since 1947. This was the first year of KEC

attendance at the CEEC.[31] The links of the EECMY leaders to

the CEEC, which the Kambata churches were part of,

were spelled out by this elaborate indigenous Ethiopian presentation.

The main

decision of the EECMY Executive Committee was to help the KEC-2 according to

its capacity and to approve of a provisional budget for this purpose.

Another

decision was to call some church leaders from the KEC-2 to Addis Abeba for

education in church administration and an introduction to the constitution of

the church. The Executive Committee

delegates were also encouraged to take a copy of the budget and try to find

support for it in their synods.[32] Lastly the delegates unanimously

decided to inform the SIM of the EECMY decision to help the KEC-2 according to

its petition.

This was

the final step in a row of decisions taken on by the KEC-2 since the EECMY

General Assembly in January 1961. The process of decision-making described

above shows what a delicate and challenging question the KEC-2 s application for membership was to the EECMY. In fact, it

dominated the EECMY second Executive Committee totally. By this decision in

June 1961, the EECMY character of an autonomous all-Ethiopian church was reinforced. The somewhat adventurous

decision by the KEC-2 rekindled the CEEC legacy of an enthusiastic Ethiopian

Evangelical Solidarity in the

EECMY. The caution among EECMY leaders, which had been generated by missionary

comity since the CEEC in 1956 and onwards, was now

definitely on the decline.

Ato Emmanuel Gebre Selassie

Links Kambata with Geneva

Ato Emmanuel Gebre Selassie was a key person in the CEEC and in the AAMY. In 1952 he had been sent to

Hosanna by the CEEC on a reconciliation mission to the

Kambata churches.[33] At the LWF/Commission on World

Mission s (CWM) annual meeting in Berlin July/August 1961 he,

as the first Ethiopian ever, gave the EECMY Field Report on Ethiopia. He did it in the capacity of one of the six

members of the LWF/CWM and as the chairman of the Ethiopia Committee .[34]

Ato

Emmanuel was indeed the right person to present the EECMY Program on Kambata to the LWF. The minutes speak for themselves:

Upon

recommendation of the Ethiopia Committee, CWM, Resolved

a) That CWM encourage

the Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus

in its plan of assistance to the Kambata Christians;

b) That CWM refer to the Budget Committee the request for

$ 14,800 - for 1962 . . . .[35]

This sum was altered to $ 13,754, . . . taking into consideration local

contributions of $ 1,000 . . . It was included in the 1962 LWF/Department of World Mission (DWM)

Program Budget as an expenditure called Educational Program, Kambata, Ethiopia 13,754.00 .[36] This meant that the EECMY request

for the Home Mission Program 1962, which in Ethiopian was $36,885,

had been approved by the LWF/CWM.[37] The detailed budget of the Kambata Program had the following structure:[38]

1.

Evangelist Training Center

(12 months) E$ 16,875.

2.

Elementary School. Elementary School Boarding 7,400.

3.

Six Scholarships - Debre Zeit 1,800.

4.

Bible School (12 students) 7,210.

5.

Teacher-adviser (300x12) 3,600.

First Year

Needs E$ 36,885.

With this budget, one of the fundamental SIM-principles applied in the Kambata/Hadiya region, i.e., not to pay for Ethiopian

indigenous enterprises with foreign money, was abandoned.[39] Salaries for an adviser, two

pastors, two teachers, and guardians had been

included in the budget for 1962.[40]

There had

not been much discussion in the EECMY on this change of principles in the Kambata/Hadiya region, in addition to the deliberations

prepared by Schaefer and Lundgren.[41] They had posed the question on how

to provide help . . . without destroying the self-governing, self-propagating, self-supporting nature of the Christians already there. [42] When discussing church-mission

relations concerning the EECMY on an earlier occasion,

Rev. Lundgren was anxious not to build a church that would depend on mission

budget. All churches and schools should be built by congregations, and all

workers should be employed and salaried directly by

the church. This was what Lundgren opted for, but the principles should be used

wisely.[43]

It seems

that there was neither enough time nor enough interest for such a discussion in

the EECMY, when it came to the point. Here again the EECMY leaders acted

pragmatically and with an Ethiopian purpose. From now on, Ethiopians would pay

salaries to Ethiopians with foreign funds in the KEC-2.

A Picture of the KEC-2 in

1961

In 1961 the KEC-2 had been on its own as an independent church for eight years.[44] As a whole, it still was very

similar to the KEC except on its teaching on moral and traditional issues.[45]

Polity: The KEC-2 consisted

of five sevens (districts). The

two strongest were the Dodoba Seven with Ato Zelleke Luke s congregation in Hawora, and the Abonsa

Seven with Ato Ashebo Wolecho s

congregation in Mishgida. The Endara

Congregation north of Hosanna in the Lemu Seven and the Sorgago

Congregation in the Soro Seven were places of interest, too.[46]

Four times a year, baptisms were held at quarterly meetings.[47] These

meetings can be compared to kinds of KEC-2 General Assemblies . The KEC-2 was

heavily dependent on local elders. The model was

conservative and authoritarian.

Worship: As there were

almost no church buildings, the services were held in private homes and thus

became dependent on the good-will of the house-owner/house-elder.[48] Singing

and prayer in local indigenous manner dominated KEC-2

services and liturgy.

Doctrine: When the link to

the EECMY became stronger in 1961, the interest in following EECMY practices on

baptism increased among KEC-2 leaders. But as no mission or the EEC /EECMY had yet come

to the Kambata/Hadiya region to teach the KEC-2, and

as the educational level of the KEC-2 elders and leaders was

very low, three years of schooling or less, not much teaching was accomplished

in the church.

Instead, the legacy of the SIM, where confession was emphasised in

connection with the sacraments, still lingered in

1961. The KEC-2 form of baptism was immersion in a river and a baptisand

was expected to profess . . . Jesus Christ as his personal Savior publicly . .

. . [49] Then he

also became a communicant.

Because liberalism on moral issues was common, the KEC-2 s legacy of

public confession became formalistic and confusing. The contradiction between

profession and practice made the KEC-2 vulnerable.

Ethos: The KEC-2 attitude

on drinking and polygamy was liberal.

Ecumenism: At a national level, the KEC-2

delegates had been attending each CEEC in Addis Abeba from 1955 to 1961. The CEEC at

this time functioned as a lifeline of moral support to the KEC-2 but the CEEC

representatives did not involve themselves actively in the Kambata/Hadiya

region. Since 1961 the KEC-2 was happily aware of an increasing support from

the EECMY. Ato Zelleke and Ato Ashebo and others met with AAMY elders in Addis Abeba on January 18, 1961. This was

the final step of the KEC-2 open acceptance by the EECMY.[50]

In April

1961, the EECMY Special Commission to Kambata visited

all five sevens of the KEC-2. In June, when the

EECMY support to the KEC-2 received official status, six elders were invited to come to Addis Abeba in July to

study the EECMY Constitution and church administration.[51] These things were anticipation of

what was to come, and filled the KEC-2 leaders with

optimism.

![]()

At the local level, the KEC-2

leaders opinions of the SIM and the KEC were critical. The KEC-2 felt

discriminated against.

Size: In 1961 the KEC-2 claimed to have twenty

congregations in each one of the five sevens and a membership of 25,000. This

was probably a huge exaggeration as 100 congregations normally would be

estimated to approximately 10,000 members.[52]

Qes Gudina Tumsa s Contribution in the Kambata/Hadiya Region

The Double Strategy of the EECMY

The framework of the Kambata Evangelical Church 2 (KEC-2) since 1962 was the

Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus (EECMY) with its four synods and church officersofficers

in Addis Abeba. In 1962 the EECMY developed what I call a double strategy in

its contact with the KEC-2.[53]

One part of the strategy was to release Qes Gudina Tumsa from the Shoa and Eastern Wollega Synod (Nakamte) for some time and make use of his talents in the KEC-2. His task was

to integrate the independent church KEC-2 as a synod of the EECMY.

This was a primary concern of the EECMY strategy.

The other part of the strategy was to ask Ato Zacheus Edamo

to leave the Wollo -Tigr

Synod and be appointed to the local Kambata Home Mission Program (KHMP)as executive secretary in the Kambata Hadiya region. His task was to implement various

indigenous EECMY projects in KEC-2 within the KHMP budget.

The process of communication between the KEC-2

and the different EECMY representatives would prove vital for the future. In

this next part I will follow developments from 1962 to 1964 on

the basis of EECMY minutes.

Qes Gudina Tumsa s Attempt at Integrating the KEC-2 into the EECMY 1963

As has been mentioned earlier, the EECMY already in July 1961 had begun

to educate KEC-2 elders in church administration and in the EECMY

constitution in accordance with the EECMY Executive Committee s resolution in

June 1961. This indicates an interest from the EECMY side to integrate the

KEC-2 as a synod from the very start of the more active EECMY support.[54]

A year

later, in 1962, Qes Gudina Tumsa paid a first visit to the Kambata/Hadiya region and met with KEC-2 elders.[55] Accordingly, the link between Qes Gudina and the KEC-2 leadership was already well

established when, in November 1962, the EECMY church officers wrote a letter

and asked the Shoa and Eastern Wollega Synod to send him to the KEC-2 for a longer period

of time.[56]

Qes

Gudina proved to be an excellent person to bring

trustworthy information on local developments to the EECMY church officers and,

above all, to start the integration of the KEC-2 into the EECMY. In February

1963 he went to the Kambata/Hadiya region with the

view to prepare the KEC-2 for its integration as a synod into the EECMY. As

aforementioned, this integration was the primary concern of the EECMY with regard to the KEC-2. The KHMP was meant to serve this purpose, too. [57]

Qes

Gudina Tumsa was from Boji in Wollega, born in 1929. He had been working

as the first indigenous pastor in Nakamte since his ordination in 1958. He was a strong preacher referred to

as our Billy Graham by Ato Emmanuel Gebre Selassie. With the Mishgida center in the Abonsa Seven as his base, Qes

Gudina started his new venture, which would go on for about six months.[58]

The

charisma of the tall Qes Gudina, when teaching and preaching, made

a strong impression on KEC elders. But they (and KEC-2 Christians)

were confused because he smoked a pipe. They were told that he had been advised

by his doctor to smoke due to health reasons.[59] Apparently

the theological paradigm of Qes Gudina and

the SIM ethos on worldly

practices differed on this point.[60]

After three

weeks, on March 9, 1963, he returned to Addis Abeba, where a spe cial session

with the EECMY church officersofficers was arranged. Qes Gudina gave a short report on how KEC-2 congregations

were starting to establish themselves and arrange their work properly , as

he put it. Qes Gudina presented a plan on how

congregations should be organized and the work be

directed.[61]

His

ambition was to visit as many congregations as possible in all the sevens and

teach EECMY doctrine and worship. His idea on polity was to

organize the small KEC-2 congregations into larger units. Thus

the dominance of the house-fathers in the family-based churches of the KEC-2

would be broken, and a more democratic system, similar to the EECMY model,

would be introduced. He also aimed to introduce a synod structure of EECMY

model in the KEC-2.[62]

The KEC-2 Elders Speak their Mind

Qes Gudina was accompanied to Addis Abeba by a delegation

of elders from the five sevens of the KEC-2.[63] They were angry and disappointed

with the current development of the KHMP because of two reasons. One was that the EECMY

school was built in Mishgida, close to Durame south of Mt. Ambaricho.

The other was that they felt forgotten by the EECMY as a partner. They asked .

. . why don t you ask us for advice, when you give your support? [64]

The elders, except for the one from the Abonsa Seven , maintained that there had been an

agreement in the KEC-2 to build a school in Dodoba,

northwest of Ambaricho. The elders explained that they had

not wanted to bring this matter up before, as they . . . did not want to

oppose the man, whom the EECMY had chosen and sent. Now, however, was the time

to take an authorised letter from the five sevens of the KEC-2, asking for a Bible

school and a synod center

to be established in Dodoba.[65]

As we saw

above, the two strongholds in the KEC-2 were the Abonsa

Seven and the Dodoba

Seven . The EECMY General Assembly, held

in January 1963, had resolved to buy a centrally located plot of land in the Kambata/Hadiya region. The KEC-2 elders then wanted to challenge the EECMY on that

decision.[66] In fact, Dodoba

is situated in the center of the region and, in 1963,

was in the actual center of the KEC-2. Some of the

elders obviously meant that Dodoba ought to become

the center of the synod-to-be.

This KEC-2

approach to the EECMY was an important event. It was in fact a demonstration of

its local legacy of independence, with links to Ambaricho and Shonkolla. The KEC-2 elders wanted to re-establish a direct contact with

the church officers of the EECMY to regain their authority with

regard to the KHMP representative.[67]

After all,

the real leaders of the KEC-2 were the elders. They had been accustomed to

attending the CEEC meetings since 1955 and to consulting the

EECMY directly. Qes Gudina obviously was in favor

of the direct approach of the KEC-2 elders to the EECMY. He understood that his

plan on integration would not be successful, if it did

not get the support of the majority of the KEC-2 elders.

What is

illustrated here is a failure of the EECMY in its early communication with the

KEC-2 on at least two points:

1. The EECMY

church officersofficers neglected the importance of a

direct contact with the KEC-2 elders instead of unilateral contacts with their own

KHMP representative. This made the KEC-2 elders

frustrated.

2. The relation

between the KHMP Director, Ato

Zacheus, and the KEC-2 elders had not been sufficiently spelled out by the

EECMY. Thus, Ato Zacheus did not base his decisions

on proper consultations with the KEC-2 elders.

The EECMY s

lack of communication had brought the KEC-2 elders to Addis Abeba. As an outsider Qes Gudina sensed their disappointment. Now the KEC-2

elders used Qes Gudina as a spokesman in an

indigenous KEC-2 effort to get things sorted out with the EECMY church officersofficers. I identify their interaction as a test of

Ethiopian Evangelical Solidarity.

Restructured Congregations

Qes Gudina s option provided a comprehensive

attitude towards his attempt to integrate the KEC-2 into the EECMY. He returned

to the Kambata/Hadiya region together with the KEC-2

elders. Soon after, he set up a team in order to implement his plan to reconstruct the KEC-2 into

a less family-dominated form and to introduce democracy in accordance with the

EECMY constitution and by-laws.[68]

The team

was led by Qes Gudina himself. Ato Tamru Segaro was used as

his interpreter, as Qes Gudina spoke Amharic and not

any of the local languages. He could not use his own mother tongue, Oromiffa. Ato

Marqos Gobebo from Dodoba, and the evangelist of the Abonsa

Seven , Ato Mattheos Dattago, were the other members of the

team. Ato Zacheus was just an outside supporter.[69]

An

ambitious visiting program was arranged in order to

preach, teach on the EECMY constitution, and rearrange the KEC-2 at the local

level. The five sevens were visited in turn. However,

neither the effort to rearrange the KEC-2 family churches into larger units

was a success, nor the so-called organisation of the sevens into EECMY

parishes.[70]

As already

mentioned, the KEC-2 congregations usually met in ordinary houses or huts. The house-father accordingly had a strong influence on the

congregation, which he was not willing to discard. If a so-called proper

church was built outside his land and a new set of elders was chosen, he and his colleagues might risk

losing their influence. It seems as if the team members had to abandon the idea

of bringing smaller congregations together, owing to a stubborn resistance to

this enterprise. Instead they concentrated on

rearranging the KEC-2 at a higher level.[71]

A Synod Structure

In April and August 1963 Qes

Gudina arranged two conventions where he tried to

apply a synod structure to the KEC-2. At the first Synod Assembly at Mishgida in April (Miazia

17-19), the purpose was to introduce the constitution and by-laws of the Shoa

and Eastern Wollega Synod in the KEC-2, and to elect a president and a

secretary.[72] From the sources available, I

identify three administrative levels of a kind of EECMY set-up :[73]

1.

A

Synod

Assembly with two representatives from all the congregations in the KEC-2 was

the wider base. The number of delegates could amount to approximately eighty

delegates.

2.

An executive committee, consisting of five

church officers plus eight other delegates. It was called: The Board of the Kambata Church .

3.

The KEC-2 conventions first elected three

church officers, who soon were extended to five.[74] The first church officers of the

KEC-2 were the following:

President Ato Tamru Segaro Abonsa Seven Mishgida

Vice-President Ato Zelleke Luke Dodoba

Seven Hawora

General

Sec. Ato

Marqos Gobebo Dodoba Seven Dodoba

Assistant

Sec. Ato Wondafresh Selato Lemu Seven Endara

Treasurer Ato Erjabo Handiso Dodoba Seven Dinika

We note that the stronger sevens Dodoba (3), Abonsa (1), and Lemu (1) were represented among the church

officers. Qes Gudina s interpreter Ato

Tamru, who was the best educated of the

five men, was elected President.

Most of the

Church officers were probably of Kambata origin, but

as already mentioned, Dodoba created a middle ground for both Kambata and Hadiya. Dinika, for example, is close to Mt. Shonkolla. Ethnic borders were less strict in

such areas and sometimes even hard to define. According to my sources, Ato Erjabo Handiso s father, for example, was Kambata

but his mother Hadiya. Ato Erjabo

speaks both languages well. From a patriarchal point of view, he is a Kambata but one may ask what such

a definition really explains. Mixed marriages and other close relationships

make the picture rather complicated.[75]

With the

new arrangement the KEC-2 elders desire to regain influence had

been satisfied. The outline of an EECMY synod structure had been introduced to

the KEC-2, at least on paper. From now on, the KEC-2 was now and then referred

to as the Synod , by the EECMY.[76]

The

transformation of the KEC-2 into an EECMY synod structure had been a very fast

process. The rearrangement of the KEC-2 congregations into larger units created

new tensions. The future would prove how wise the new measures were.

Ambivalent Primary Concerns

The double strategy of the EECMY influenced the

KEC-2 to a great extent. Its primary concern was to integrate the KEC-2

into the EECMY synod structure. Accordingly, the EECMY strategy favored an integration of the KHMP and its Di rector into the new KEC-2, or

the so-called Synod , and under the KEC-2 Church officers.[77]

Ato Zacheus implemented the KHMP strategy through the support of various

projects. He was a key person in the process of communication between the EECMY

and the KEC-2. He felt content with his position as Director of the KHMP. It

is apposite to suggest that his primary concern was not to reduce his own

influence in favor of the newly elected KEC-2 Church

officers.

Qes

Gudina s arrangements for a KEC-2 synod

model created a new leadership structure in the KEC-2. On the one hand, the

KEC-2 elders were eager to transform the KEC-2 into an

EECMY synod. On the other hand, the KEC-2 had a legacy of a congregation-centered polity and a mobile leadership of elders, which was

appreciated by many. Thus, Qes Gudina s

rearrangements were not happily received by all KEC-2 members. When he left the

KEC-2 in the summer of 1963, he left two strong bodies of the KEC-2 behind him.

One body

revolved around the KHMP leader Ato Zacheus and the Abonsa

Seven . The other body was the new KEC-2

Synod led by the Church officers with a majority of its members from the Dodoba Seven . They were keen to demonstrate the

central importance of Dodoba compared to Abonsa. The former body was then expected to coordinate its

efforts and projects more closely with the latter. In fact

the KHMP was subordinate to the KEC-2 and its Church officers. At that time,

there was also a third disappointed body , i.e. the elders, who had lost their positions

because of Qes Gudina s new arrangements. They were the

losers and fanned the flames of discontent with the new order whenever an

opportunity occurred.[78]

Indeed, the

EECMY double strategy was hard to realize.[79] In fact Qes

Gudi na s short, intense campaign opened up an implicit tension.

An Issue of Relevant Contextualization

The KEC-2 was a church that earlier had reacted to pressures from

outside. Its negative reactions to the KEC (SIM) were mainly generated by

cultural reasons. As already has been mentioned, the KEC-2 evolved as an

independent church owing to such reasons.[80]

The

problems confronting the EECMY in its realization of its double strategy in

the KEC-2 can be described from different perspectives. One perspective is to

describe them as due to a lack of EECMY understanding of the KEC-2 context and

thus a failure of contextualization of the KHMP efforts into the KEC-2 reality.[81]

As already

mentioned, the young EECMY showed little interest in the Schae fer and Lundgren deliberations, which emphasized a

preservation of the KEC-2 s indigenous legacy. The shift of principles from not

paying salaries from external funds to indigenous work, applied by the SIM for

years in the Kambata/Hadiya region, to the opposite,

was not carefully assessed by the EECMY.[82]

The

centralized EECMY approach with a dominant KHMP leader was foreign to the KEC-2 collective polity built on elders. The KEC-2 elders may have asked:

Is it recommendable to let one man employ people and pay their salaries in a

fast-expanding program? The idea of collecting money into a centralized budget

had been a main reason for the KEC split in 1951. When this idea eleven years

later came dressed in KHMP clothes , it did not look much better to the KEC-2.

Why, did the EECMY introduce such a foreign idea

anew? The collecting and sending of money to an unknown place filled KEC-2

Christians with suspicion.

Why, were

some prominent people like the KHMP Director , the KEC-2 President, and the KEC-2

Secretary receiving salaries, while others were not? How could someone believe

that the Kambata/Hadiya farmers would support such a

foreign idea? The KHMP was interested in quick results. The KEC-2 procedure was

slow and demanded considerable time for discussions.

The new

synod structure of the KEC-2 was furthermore foreign to the KEC-2 indigenous

ideas. The KEC-2 elders were used to a mobile system of meetings,

visiting all the sevens in turn. The EECMY approach was to

make one place, Mishgida, a dominating center.

This reinforced tensions with other sevens , especially with the other KEC-2

stronghold Dodoba.

The EECMY

system of a centralized democracy, with five Church officers as dominating

representatives, brought new ideas too fast into the KEC-2 pattern of

collective leadership. The KEC-2 indigenous leadership with all its

shortcomings had the support of the KEC-2 elders and ordinary Christians. This was hardly the

case of the new KEC-2 in its EECMY synod set-up in 1963.[83]

Roots of New Conflicts

It seems as if the centralized approach of the EECMY to the KEC-2 in

1962-64 and the lack of contextualization were major reasons for the problems generated

in the early period of more intense EECMY/KEC-2 relationships. One cannot speak

of a long-range plan on the part of the EECMY in its behavior

towards the KEC-2 in 1962-64. On the contrary, the pace of the EECMY actions

seems to have been guided by the LWF budget process. When money was available,

EECMY chose a suitable man, Ato Zacheus, and appointed him the KHMP Executive Secretary.

Qes

Gudina was sent to the KEC-2 from an unsolved

conflict in Nakamte on his way to studies abroad.[84] He made a concerted effort in the

KEC-2 and used a model familiar to him, that is, the Shoa and Eastern Wollega Synod Constitution and by-laws, as a means of

reorganizing the indigenous independent KEC-2. He was in a hurry as he was

going to leave the country. He probably had little time for reflection on the Kambata/Hadiya context and the KEC-2 legacy.

The lack of

understanding of the KEC-2 legacy and its context on the part of the EECMY at

this early stage proved to be very negative to the KHMP results in 1962-64. The evident problems of

communication experienced by the EECMY Church officers in their contacts with

the KEC-2 and local KHMP representatives were signs of this lack of

contextualization. Ato

Zacheus s central position and his favoring of the Abonsa Seven were already established when Qes Gudina started his mission with a view to implement

EECMY democracy. His arrangements came both too late and too early. Actually, they reinforced an inherent conflict and further

dissonance.

It is

tempting to try to find simple explanations and scapegoats when analyzing conflicts of this kind. This can hardly be done in the complicated

framework of the EECMY - KHMP - KEC-2 interaction with its various aspects.

The idea of the KHMP was to bring educational, administrative

and spiritual support to the KEC-2. Furthermore, the EECMY aimed at integrating

the KEC-2 as one of its synods. Yet, the EECMY Synods in 1961 and onwards were

in fact in need of the same support as the KEC-2 when they now enthusiastically

were trying to bring it into the EECMY.[85]

The KHMP generated positive results, too. Yet there

were obvious weaknesses in the EECMY approach to church problems in the Kambata/Hadiya region. The results of the KHMP were not as

good as the EECMY had expected. From the autumn of 1964, this state of affairs led the EECMY leaders into a period of

analysis and reflection on how to continue its operations in the Kambata/Hadiya region.

The EECMY

change of attitude to the KHMP can be illustrated by the EECMY reports

delivered to the annual CWM meetings of the LWF for the years 1962-64.

Ato

Emmanuel Abraham proudly describes the EECMY involvement for

the year of 1962 in a written report:

Although

the church is a very young church, it has not neglected to initiate its own

home mission program. In the Kambata

area of Ethiopia, it has established, with the help of the LWF a home mission program which is directed by

the church and has no foreign missionary personnel serving in it. There are no

exact figures as to how many are now seeking admittance in the church in this

area, but estimates run from 25 to 45,000 individuals. The church has

instituted a five-year program during which time it hopes to be able to

organise, teach and bring into the church those in Kambatta

who have declared themselves so interested.[86]

The new

EECMY Executive Secretary, Qes Ezra Gebremedhin, made the following presentation

for the year of 1963:

The home

mission program of the church in Kambatta

is proceeding under the leadership of Kambata

Christians. In the year 1963 a synod was organised, a new elementary school

completed and a literacy campaign launched.[87]

The report

for the year of 1964, which was

presented by Qes Ezra, did not mention the KHMP.[88]

A Picture of the KEC-2 in

1962-63

In 1962 the independent church KEC-2 had set out for an unknown destiny. This

Ethiopian church tried to adapt to an EECMY synod structure. This was

especially the aim of some leaders and elders who tried to direct its course. The real

dynamics from our point of view, however, were hidden. This part of the KEC-2

was not that easy to influence.

Polity: The transformation

of the KEC-2 leadership functions, from a more flexible, collective system

based on consensus and long discussions to a more centralized administrative

system based on democratic principles of majority voting, was introduced by the

EECMY pastor in Nakamte, Qes

Gudina Tumsa. In the spring of 1963, he led an

intense campaign that aimed at rearranging the KEC-2 according to EECMY

patterns.

In the summer of 1963, the KEC-2 adopted an EECMY synod structure

consisting of three administrative levels, hence from now on it was

occasionally referred to as the Synod :

A Synod Assembly ,

which corresponded to the former quarterly meetings, consisted of two

members from each congregation in the KEC-2.

An executive

committee consisted of the five Church officers plus eight others. It was

called The Board of the Kambata Church . It corresponded to

a certain extent to the monthly meetings of the KEC-2.

The executive leaders

were five men called Church officers . Most of them were from the Dodoba Seven . The President and

Secretary of the Synod were paid by KHMP budget.

The KEC-2 five sevens were then taught

how to adapt to an EECMY parish (sebaka)

structure with central administrative functions. These were, however, not easy

to implement in the sevens . Instead tensions between

the KEC-2 strongholds, the KHMP-dominated Abonsa Seven and the Dodoba

Seven , increased. The mobile character of the KEC-2

leadership structure was challenged by the KEC-2 new static center

in Mishgida. A new class of paid

KEC-2 church-workers evolved.

At a congregational level, the new ideas of drawing smaller

congregations together after some time met a stubborn and even violent

resistance.[89]

Especially strong was the reaction to collect and send away money for common

purposes. This was probably due to previous experiences of KEC-2 members before

the KEC re-structure in 1952.[90]

The efforts of re-structuring the KEC-2 polity thus led to two ecclesiastical systems

competing for influence in the KEC-2 in the summer of 1963: an independent

congregation-centered collective KEC-2 type and a

centralized administrative EECMY type. The competition fanned the flames of

discontent in an evolving multi-facetted conflict, which was induced by the new

KHMP budget-system introduced into the KEC-2. The

tensions generated a big conflict, which shook the KEC-2 from the summer of

1963.[91] Numerous

conflicts between elders of smaller congregations were reinforced by

former discontented elders, now losers in the new system, and the poor

examples set by the new KEC-2 Synod s top leaders Ato

Tamru Segaro and Ato Zacheus Edamo.[92]

Doctrine: Subjective aspects

of faith dominated KEC-2 doctrine. Qes

Gudina s teaching was actually the first time ordinary KEC-2 Christians and local elders were influenced by a systematic EECMY teaching

on the sacraments. Qes

Gudina, furthermore, emphasised the necessity to start Sunday schools and

confirmation classes in the congregations.[93] When it

was functioning, the Bible school provided traditional basic knowledge in the

Scriptures, probably augmented with some Lutheran doctrine. As the Bible school

itself was a tool in the conflict, its teaching was not effectual, however.

Ethos: The KEC-2 attitude to drinking and

polygamy was liberal.

Relations to the EECMY: At a national level, the KEC-2

elders and Church officers from 1963 took part in

the EECMY General Assemblies and executive committee meetings. At the regional

level, there was a flow of Ethiopian contacts between the KEC-2 and the neighboring NLM-related Sidamo and Gamu Gofa Synod. Scholarships were distributed for

education in different institutions. At the local level, the lack of

contextualization of the EECMY approach led to strong reactions

against the EECMY novelties. This had not been anticipated by the EECMY

representatives.

![]()

Size: In 1963 the KEC-2 membership was estimated at

about 30,000. As in 1961 this was a gross exaggeration.[94]

There were still five sevens in the KEC-2.

Qes Gudina Tumsa Connects FMS with the KEC-2,

1967-69

After studies at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota 1963-66, Qes Gudina returned to Ethiopia and served the EECMY as its

General Secretary from 1966 to 1979.[95] With his widening perspectives, he

resumed his efforts to support the KEC-2 in becoming a synod in the EECMY.

Heart-searching questions on the continued financing of the

Kambata Home Mission Program (KHMP) and its integration into the KEC-2 had forced Ato Djalatta to begin to contemplate the possibility of the

direct involvement of a new missionary agency in the joint EECMY-KEC-2

enterprise in the Kambata/Hadiya region. Continued

developments resulted in a new venture by the Finnish Missionary Society (FMS).[96]

In Africa

the FMS was hitherto mainly involved in Namibia and Tanzania. The EECMY with its international

connections took the initiative in the contacts with the FMS. In this new

process, the KEC-2 was simply at the receiving end.

It is this

development that will be the main preoccupation of this part of my paper. In

addition to the EECMY minutes, I mainly base my account on primary sources in

Finnish from the archives of the FMS, nowadays called the Finnish Evangelical

Lutheran Mission (FELM).[97]

The FMS Arrives in Ethiopia

On June 5, 1967 the FMS General Assembly decided to let the FMS Board

make arrangements for the start of a new involvement in Ethiopia, but it was

not yet fully committed to the Kambata/Hadiya region.[98]

When the

EECMY prepared the FMS survey in Ethiopia, it planned to present two

options, the Kambata/Hadiya region and the Western Wollega Synod (WWS).[99] However, the LWF preferred the FMS to choose the first. This is

further illustrated by a personal visit paid by Dr. Hellberg to the region in the rainy season of 1967.[100] On August 15, 1967 he

was able to report on his visit in the region to the EECMY Church officers. In

this time, he had actually travelled in the hilly

country from Durame to Hosanna on slippery roads mainly on mule, a distance

of c.60 km. His guides were Qes Gudina Tumsa and Ato Djalatta Djaffero.[101]

Dr Hellberg s impression was . . . that Hosaena would be a suitable location for a future Synod

Office as well as for the Bible school . . . . [102] There were many reasons for this,

but communication and light were the two mentioned. Astonishingly, according to

the EECMY minutes, nothing was said of the KHMP centre in Mishgida/Durame or the consequences for the work when the center was changed from the Kambata

area to Hadiya area. Dr Hellberg just limited himself to suggesting:

. . . that

in case the Finnish Missionary Society would undertake the work in Kambata, CWM would be in a position to give favourable

consideration to the request submitted to CWM/LWF in the five

year plan.[103]

This was a

clear message from the LWF to the EECMY. According to the EECMY, the LWF

had agreed to support the KHMP at the LWF/CWM meeting in April 1967 if a supporting mission was found. In August the FMS was explicitly recommended as such a mission.[104]

A three week trip,

October 16 - November 7, to Ethiopia had been prepared by the EECMY for the FMS delegates Rev. Ojanper and Rev. Remes. October 17-23 was set aside for a

survey of the Kambata/Hadiya region, October 24-31

for the WWS. One week would be spent in Addis

Abeba, including a meeting with the EECMY Church officers on the day before

their departure.[105]

EECMY Leaders Introduce the Kambata/Hadiya

Region to the FMS

On October 17, 1967 the FMS delegation went by plane from Addis Abeba to

Hosanna. The EECMY guides were Qes Gudina and Ato Djalatta.[106] It was stated that one should try

to make Hosanna the new centerof the church, and the

group visited a land-strip . . . reserved for the administration of the

church . Dodoba, which also was visited on the

trip, was not considered interesting for a Bible school any longer, however.[107]

There were

probably several motives for this new interest in Hosanna. As has been

indicated, Hosanna is a central place for the Hadiya ethnic groups, and Durame a central place for the Kambata

ethnic groups. By moving the KEC-2 center from Mishgida/Durame to

Hosanna it was moved from a Kambata centre to a

Hadiya center.

When Dr.

Hellberg in conversation with Rev. Ojanper calls Hosanna . . . a neutral place , this must be

understood as neutral in respect to the KEC-2 sevens .[108] Hosanna was not in the center of the conflicts of the KEC-2. In fact

the town of Hosanna seems to have been more or less an empty spot for the KEC-2

in 1967. In 1962 comity questions were more sensitive to the EECMY

than later on. In that year it would probably have

been complicated to place the KEC-2 center in

Hosanna, close to where the KEC/SIM center was

situated.[109] In 1967 the internal tension

between the KEC-2 sevens was a more problematic issue for the EECMY than

questions of comity, however.

It is

likely that the EECMY wanted a new start for the KHMP and the FMS missionaries to begin in more neutral ground

outside the spheres of influence of the stronger sevens of Abonsa and Dodoba and their mutual and internal conflicts. These

ideas, coupled with the advantages of having a new synod center

situated close to the Awraja center,

became decisive for the choice of Hosanna.[110]

The group

continued to the south of the region by plane, via Soddu, the capital of Wollamo. At the Mishgida center, they visited

the Bible school with its thirteen students. It made a poor

impression on the Finns. The Mishgida School was more impressive with its 450 students.

After the stay in the Mishgida center,

they visited four small congregations in the Abonsa

Seven . These were Ambo, Abonsa, Djore, and Adilo. Then the group returned to Addis

Abeba via Shashamene and the NLM agricultural school in Wondo.[111]

The FMS Delegates Meet

the EECMY Church

officers

When the FMS representatives met the EECMY Church officers

in Addis Abeba to discuss the FMS engagement in Ethiopia, the following persons

received them: Qes Gudina, Ato

Emmanuel Gebre Selassie, Rev. Lundgren (SEM), and Mr. Magnar Mag er y (NLM). The Finnish delegates raised the

question of comity as a possible obstacle to working in the Kambata/Hadiya region.[112] They had been told by Mr. Hod ges of the SIM that concerning comity regulations

the SIM:

. . . did

not want to forbid anyone to come, but would on their

part go on working on their own. He argued that the

Comity committee had allotted Kambata to the SIM.

Naturally there have been confrontations with other missions.[113]

The EECMY s

answer to the FMS delegates reflects

Ethiopian independent mentality, which opposed the missionaries comity constructions. The Finns were accordingly

advised . . . not to bother too much about the SIM-work there, as no mission

has any special rights to the said area. [114] The goal for the work in Kambata was to build a national church. A new missionary

society was not needed, but workers sent by the FMS, were willing to work

under the EECMY.[115]

The

immediate need for personnel was further specified: an adviser, with experience

from another part of Africa, a teacher for the Bible school and a builder for a shorter period. It was

emphasized that there was need for investments both in personnel and economy in

the Kambata/Hadiya region. Rev. Ojanper realized that the EECMY was keen to get the

FMS engaged in the region.[116]

There was a

certain ambiguity as to what was expected from the FMS, however. When confronting the

issue of comity raised by the SIM, and while talking on

integration, it was stressed that the mission was under the EECMY and that

the missionaries were just co-workers in the church. When it came to concrete

expectations, the FMS was expected to make a huge input of money and personnel.

Thus, Qes Gudina stressed that if the EECMY did not invest in

personnel and money as in other synods, one could not expect any better

results. Ato Djalatta, who was not present at the Church

officers meeting, had for his part said that the new five-year plan would be

dependent on what the LWF and the FMS wanted to do. He hoped that the builder, the

adviser, and the teacher would soon arrive.[117]

It seems

that the two men with the closest knowledge of the KEC-2, i.e., Ato Djalatta and Qes Gudina, had quite a pragmatic view of the

FMS enterprise in the Kambata/Hadiya

region. Others were more concerned with ideology. The words above of not

sending a mission to the region and building a national church are vague when

considering the specific needs, which had been presented earlier to the FMS

delegates. They can be specified under the following three headings:

1. Spiritual needs: About 80-100 new evangelists

were needed for the KEC-2. The place of teaching should be in the Kambata/Hadiya region and it was

going to be given on two levels. One for students who had finished the third

class, and the other for students who had finished the sixth class.

2. Educational needs: Hostels were needed in Mishgida and in Hosanna. The other five sevens ought to have a

six-grade school of their own. Scholarships were needed. A vocational school

combined with an agricultural project would be welcome.

3.

Medical needs: A small hospital with fifteen

places was needed, and at least one clinic in each seven .[118]

Nothing had been said about who would meet

these needs except that the EECMY responsibility had been stressed. It is

reasonable to conclude that it was implied that the FMS was to supply the budget for the new projects,

hopefully together with the LWF. The EECMY leaders knew that the

LWF was interested in reducing its involvement in the KHMP-project, and the FMS delegates must

have been realized this by the FMS delegates at the 1967 CWM, too.[119] According to the FMS minutes,

though, the EECMY had agreed with Dr. Hellberg that the LWF would provide the budget at the

initial stage if the Finns sent personnel.[120]

What about the KEC-2?

According to available sources, the KEC-2 kept a low profile during the

FMS explorations of the Kambata/Hadiya

region. The presentation of the region was made by two Oromos - Qes

Gudina and Ato Djalatta. Ato

Geletta Wolteji s name is

also mentioned in the FMS report.[121]

In fact,

not one person from the KEC-2 or one local leader of the region is mentioned by

name in the Finnish report. In a similar way no one from the KEC-2 was present

when the FMS discussed the Kambata/Hadiya

region with the EECMY Church officers. The leader of the KEC-2 Bible school, Ato Leggese Segaro, obviously was English-speaking as

he was a graduate from the Mekane Yesus

Seminary. The KEC-2 President, Ato Erjabo Handiso, was most

certainly around. Neither of them is mentioned by name in the Finnish report.

The short

visit by the team to Dodoba conveys the impression that this place, which

for so long had been planned to be the site for a Bible school, was not of special interest any

longer. After all, this was the place where the majority of

the current KEC-2 pastors had been ordained by Qes Ezra Gebremedhin in 1965. Then, however, it seems

to have been regarded as situated in the middle-of-nowhere.[122]

Was the

move of the KEC-2 center from Durame to Hosanna ever properly discussed with the KEC-2? Or was

it just decided at a higher level ? I suggest that the latter is the case.

Thinking of the prevailing conflicts in the KEC-2, it may have been a wise

decision of the EECMY to let the KEC-2 representatives keep a low profile in

their presentation of the Kambata/Hadiya region.

Anyhow, one must admit that it was not an integrated presentation from a KEC-2

point of view. It was planned and arranged by EECMY officials on a national

level in Addis Abeba.

No strong

objection from the KEC-2 side on this state of affairs

can be traced though. It was then on its way to get a supporting foreign

mission. This was the vital issue for the KEC-2 in 1967.

The FMS Delegation Faces the Challenge

The FMS delegates were challenged by what they had

been introduced to in the Kambata/Hadiya region. They

were not to register as a mission, but to start its work as a part of the

EECMY. This was very much in line with theological discussions on the

integration of missions into the EECMY in Ethiopia in 1967.[123]

The

American Lutheran Mission (ALM) signed a document of such an

integration with the EECMY and the Wollo-Tigr Synod on May 29, 1966. This was well known to the

other synods in 1967. Meetings and deliberations concerning the integration of

the missions into the EECMY were taking place in 1967-68. The Synod Presidents

and the Lutheran Mission Directors listened to lectures on this

subject by Ethiopian speakers such as Ato Emmanuel

Abraham, Qes Ezra, Qes

Gudina, and Ato Djalatta.[124] The FMS had the chance to become an early follower of

the ALM in this respect. This was apparently

important to the FMS.[125]

Furthermore,

the financial engagement of the LWF in the region was regarded as an asset by the

FMS.[126]

The Decision of the FMS

In 1968 the groundwork was made for the integrated FMS approach in the Kambata/Hadiya

region. Parallel arrangements were going on in Ethiopia and Finland. On April

22, 1968 the FMS Board decided to start work in the Kambata/Hadiya region.[127] The EECMY leadership welcomed the

decision at the EECMY Executive Committee meeting in June 1968. The EECMY

looked forward to welcoming two new missionaries in January 1969.[128]

At the same

meeting of the EECMY Executive Committee, the KEC-2 presented a draft

constitution for membership as a synod in the EECMY. This draft was sent to the

EECMY Synods Presidents for comments.[129] Apparently it was still felt

necessary to base important decisions on the KEC-2 within the four synods. As

this new synod would become an important part of the EECMY body with its

reported high membership, the KEC-2 merger with the EECMY had to be well established

among the other synods.

Qes

Gudina Tumsa reports to the Commission on World

Mission (LWF) at Hiller d in Denmark in August 1968:

. . . The Kambata home mission program was one of the areas which has been

absorbing much of the attention of the church. The Finnish Missionary Society

was invited to come out to assist in this challenging undertaking by the

church, and we now rejoice over the fact that our invitation has been accepted

by the FMS to start work in January 1969.

A plan to form a team to organise the Kambata congregations in a synod structure is being carried

out and it is hoped that the Sixth General Assembly of the church in January

1969 will accept the Kambata Synod as a full member of the church, a fact which

will increase the number of synods of the church from four to five and a growth

in membership from seventy-seven thousand to over hundred thousand.[130]

The feeling

of relief and joy can be read between the lines in Qes

Gudina s report. The process of

integrating the KEC-2 as a synod into the EECMY had been initiated by Qes Gudina in the spring of 1963. Now the implementation

was not far away.[131]

On October

22, 1968, the EECMY President Ato Emmanuel Abraham and the FMS Director Rev. Alpo Hukka signed an agreement between the EECMY and the FMS in

Addis Abeba. The FMS s agreement with the EECMY

anticipated the document on integration between the EECMY and its cooperating

missions, which was finally signed on April 7, 1969. The agreement stated that:

The Mission

shall work with and within the Church in accordance with her Constitution and

shall in all its work, until otherwise decided, be directly responsible to the Church

officers.[132]

It should

be noted that the agreement concerned the FMS and the EECMY. Apparently the EECMY Church

officers already considered the KEC-2 an integrated part of the EECMY. However,

the FMS relations to the KEC-2 were yet an unwritten chapter. After all, it was

not in Addis Abeba but in the KEC-2, a church in transition, that the local

integration was expected to be realized.

The FMS appointed five missionaries for work in the Kambata/Hadiya region. The leader was Rev. Kaarlo Hirvilammi. He had experience from six years of integrated

mission work in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania (ELCT).[133] The

decision to choose a FMS-missionary from Tanzania and not from Namibia was probably due to the experiences of the

Tanzanian missionaries working in a church with a similar agreement on

integration as the EECMY was expected to achieve.[134] This experience was considered to

be of great value when trying to work under the

EECMY as an integrated mission .

At the

EECMY executive committee on June 13-14, 1969 the

EECMY members accepted the KEC-2 as the 5th synod of the EECMY. It

got the name the Kambata Synod . Today, in 2011, its

name is the South Central Synod (SCS).

Conclusion

When Qes Gudina Tumsa arrived in the Kambata/Hadiya region in February 1963, there was already

an evolving conflict between the KEC-2 church elders and the KHMP and its

powerful Director, Ato Zacheus Edamo.

It seemed as if one of the sevens , that is the Abonsa seven , had received too much favor

at the expense of the other sevens . The KHMP was experienced as a foreign

body by the KEC-2 elders and was not properly integrated into the KEC-2

ecclesiastical structure. The KEC-2 elders felt that they were losing authority

and were not listened to by the EECMY, which Qes

Gudina (perhaps too late) tried to rectify.[135]

Qes

Gudina s concerted effort to rearrange the polity of the indigenous KEC-2 into what was called a proper

church , that is, into an EECMY Synod model, needed the support of the KEC-2

elders. Qes Gudina s efforts were perhaps a bit too

ambitious in the short time he could spend in the region, just six months. The

small family-based house-churches being rearranged into larger units met

stubborn and even violent resistance. The transformation of the sevens into

an EECMY sebaka (parish) structure was not easy to

implement. The idea of having a static power-center

in line with an EECMY model, instead of a mobile KEC-2 one that promoted long

discussions and great collective participation, was not favored

by many of the KEC-2 members. They seemed to have enjoyed the KEC-2 polity with

sevens , monthly and quarterly meetings , rather than the three-level

structure of the EECMY. Anyhow, by this new structure, the KEC-2 elders (now

Church officers) formally regained their influence over the KHMP (and its Director), an achievement more easily said than done. To

employ some of the Church officers by outside funds was another foreign idea to

the KEC-2 with its legacy of self-support in line with indigenous principles

introduced early on by the SIM. In fact the KEC-2,

though weak, was self-supporting before the LWF program started in 1962. Even

worse was the idea to collect money to a centralized budget. That reminded the

KEC-2 members of one of the crucial motives of the split in the KEC in 1951.[136]

There was

an obvious lack of time, a lack of study of the history of the KEC and KEC-2

from the EECMY side (of which Qes Gudina was a key-person), and thus a lack of proper contextualization.

One result of the changes in the KEC-2 polity and the way the KHMP was

introduced in the region was an intense power struggle between the

representatives of the KHMP and the KEC-2, and also in

the KEC-2 itself. Though there were some positive effects of the EECMY Home

Mission , it was decided that the EECMY approach to the KEC-2 had to be

re-evaluated and rearranged, starting in1964.[137]

The

Lutheran doctrinal teaching of the KEC-2 by the EECMY was

introduced at the regional level by Qes Gudina. This

teaching would take a long time to be grasped and implemented among the KEC-2

members, who had been brought up in a Baptist environment mixed with indigenous

cultural ideas.[138]

In 1967-69 Qes

Gudina, now as General Secretary of the EECMY, once more played an important

part in the process of merging the KEC-2 into a synod of the EECMY. He became

instrumental as the one who linked the KEC-2 with the Finnish Missionary

Society. It is however interesting to notice that the deliberations of the FMS

and the EECMY was conducted at a national level. The KEC-2 was in fact just at

the receiving end of these procedures.[139]

The EECMY

vision from 1961 to support the KEC-2 was thus finalized in 1969 when the KEC-2

was accepted as the 5th synod of the EECMY, the Kambata

Synod . This process had perhaps become more adventurous than the EECMY could

have imagined.

The story

of the KEC-2 EECMY relations is an example of how an autonomous church

(EECMY) supports an African Independent Church (KEC-2) in an indigenous Home

Mission regardless of missionary comity rules. In this venture, Qes Gudina Tumsa was one of the key figures. He must be

admired for his endurance and dedication in this great challenge. Qes Gudina is still well remembered in the Kamabata/Hadiya region as one who transcended barriers of

ethnicity, social status, and denominationalism.

This way of doing mission is in line

with the legacy of the Evangelical Pioneers of the EECMY since the early

Bethel Congregation at Massawa. The early Bethel Congregation functioned as the

yeast of an expanding Evangelical counterculture in Ethiopia at the end of the

19th century, and this counterculture continued in the 20th

century in the EECMY. The concept for this type of attitude in mission can be

called Ethiopian Evangelical Solidarity .[140] Qes

Gudina Tumsa s ministry in the Kambata/Hadiya

region is a good example of this attitude.